Emergent Edges

Ten full moons have fallen since I published “Mother Yards and the Native Plant Sharing Network.” The ideas I proposed in that post are unfulfilled, but holding fast—assuredly waiting for warmer days to spark their emergence. Today, though, it’s cold and wintry, and I can feel the chilling distance that separates those ideas from the world we live in. I’m not sure how to bridge the gap, or if it can be bridged, but I am here taking the first steps, writing the first words to see where they lead. That’s where we’re going – and plants will take the lead. To honor plants in this essay, I will be using “ki” as the personal pronoun for any plant or other non-human being that we commonly refer to as “it.” Referring to a tree or any living being as “it” is both disrespectful and habitual; I am trying to break the habit. The suggestion for the use of “ki” rather than “it” comes from the work of Robin Wall Kimmerer.1 “It” has no life, but ki is, ki is, ki is!

The Emergent Edge

The emergent edge is plant life arising, then moving forth: a solitary aster maturing and releasing ki’s seeds into barren soil, a colony of blueberries spreading by burrowing underground sprouts, a verge of woodland creeping inward to succeed the herbaceous plants in a sunny forest opening. It is the confluence in which the edge of the wild encroaches upon and mingles with human settlements to form the welt. It is life longing for life through the intangible space where plants appear from the other world into this world.

The Native Plant Movement is Being Routed

Although our native plant movement is slowly growing, we are fast losing the greater planetary struggle to preserve native plants and all of biological life. The unceasing expansion of human settlements is obliterating any gains made through the movement, and much of that rout is taking place along the edges of the wild. That’s where ever-bigger bulldozers are extinguishing the emergent life forces in those edges. Our local news is too often headlined with stories of local zoning boards revising zoning codes to allow for the building of more homes, more businesses, more infrastructure. The inevitable, tragic result is the relentless destruction of woodland and agricultural land, a wave of ecological devastation we cannot possibly remedy with community native plant sales and sparse attempts to garden with native plants. Only arrogance—or naïveté—could allow us to see otherwise. Yes, I know both—and both are blinding.

Landscaping with native plants has been the mainstay of my life’s work for the past two decades. I bought into the concept, the entirety of it, but finally, belatedly, I have seen through the delusion that enabled me to presume that my work was significant enough to advance the healing of the earth. It’s just not enough, and it will never be enough, to counter the ruinous consequences of continued land development. This land of oak and hickory and maple, this land of squirrel and possum and crow, this land is our homeland, it’s the land that sustains us, and if we have any hope of preserving and restoring it, we must halt development’s destructive surge, and get native plants moving through the community on a scale of which our native plant nurseries and native plant gardeners are neither equipped nor empowered to carry out. We must face ourselves, peer through delusional mist and acknowledge that in the chronology of life’s emergence on earth, plants inhabited the planet long before people; then we must stare down exactly what that means.

Yes, plants came first, and we must allow plants to lead nature’s restorative movement. If we let plants guide us, they will show us what to do, and that change will fundamentally recast our relationship with plants—for the good of all biological life. How did we surmise that we know more than plants about the ways of healing the earth? How did this knowledge come to us—we, the offspring of the movements, migrations and voyages that brought us here from distant lands—we who have unceasingly subjugated the plants of this native land and then surrounded ourselves with exotic plants from far-off places that have little to no natural connection to the land we now claim is ours?

Walking in the Footsteps of Native Plants

The concept of emergent edges arises out of the extant species of our native land. It’s not about which specific native species we choose to plant, when we choose plant them, or how we choose to plant them. Rather, it’s about having the courage to take our foot off nature’s neck and allow life to unfold naturally, as ki wills to do, to heal the planet. Allowing always honors the inherent knowledge of the local land; it’s in the collective DNA of the inhabiting species. Observing the emergent edges unfolding, we can learn about the process of land healing; we can see what plants are best for initiating and fulfilling the restoration, and how those plants weave themselves together to make a sustainable whole. We must discover how to live and work in their space, in the welt, on the edge of the wild. And it must be more than a cerebral, fanciful exercise; it must be fed by our life blood, our sweat, with blessings from nature, blessings bestowed when we walk in the footsteps of native plants.

When we begin that walk, we will soon realize that plants don’t recognize the artificial barriers we humans have created. Plants don’t observe state lines, county lines, or property divisions —their longing for life does not recognize these human distinctions. As plants reproduce, they may encounter walls and fences, but the eternal winds of evolution blow seeds right into, over and through them. This is in part what makes them so effective as earth-healers—they are impelled to flow on, continuously. On the other hand, when plants are owned and held hostage as salable property, when we place them on a shelf and detain them until they bring a set monetary value in return, when we call in the plant inspectors and begin the certification process, plants become “its” rather than kin. We biologically devalue them by curbing their movement. I know our native plant community has attracted many well-intentioned people, but if we take a hard, unflinching look at the real, historical results of our work and compare it to the staggering destruction caused by land development, we are rightly grief-stricken. Is there a better way, and who would know the better way? Perhaps, it is the native plants themselves, the plants emerging on the edge of the wild.

Aiding the Movement of Native Plants

No matter our location, we are a people living in the natural world. We live in the earth, not on it, as David Abram has pointed out.2 The native plants growing in the emergent edges of our communities, these plants are our people, our kin. They came from this land, our shared home, and we can best help restore it by aiding their migration. Advancing the free movement of plants is not charity at work, it’s nature at work—with plants leading, humans following. Our role is to become co-conspirators in their life’s purpose.

How can we become co-conspirators with plants? For one, we can establish and participate in the aforementioned native plant sharing network. The network is a way for us to ally in the unfettered movement of plants through the evolutionary mechanisms they have worked out over millennia. Plants restore the earth’s breathing, animate surface like a healing skin wound, beginning along the pervious edges and moving inward, to seal the surface. Our job is to aid their movement, to become foragers, native plant gatherers who harvest plants from the welt, in the edges of the wild, and transport them inward. There are no marketing gimmicks, no sales pitches—only foragers who honor the land, by freely following plants. “By honoring the knowledge in the land, and caring for its keepers, we start to become indigenous to place,” states Robin Wall-Kimmerer.3 We begin to make this land our homeland.

It all begins with the natural dreaming of the earth, with the seeds and sprouts that are expressed through the ancestral memory of the extant native plants in our communities. That expression unfolds through an unrelenting generative power that human efforts cannot supersede. Surely, our arrogance has created enough havoc. It is time for us to stop—just stop—and begin learning a new way of belonging to the earth. We must see that plants are not only worthy of being our partners in the native plant movement, they are worthy of leading it. The emergent edge is our teacher and ki is right outside our front door. Ki is the mother tree, ki is life longing for life, and through death, feeding life again. To become co-conspirators in ki’s movement, we must proceed as if plants came before us in biological time, as if plants are our elders.

“The gift of love is the gift of the power and capacity to love, and, therefore,

to give love with full effect is also to receive it. So, love can only be kept by

being given away, and it can only be given perfectly when it is also received.”4

This famous quote from Thomas Merton is a reminder that we too are life longing for life and love is that longing5 through which new life comes into being. The conundrum is that our love has become utterly isolated from nature; we are so completely disassociated from the wild that our love is unable to embrace the myriad other beings in the natural world. We are stranded on a biological island. It’s an island that our persistent subjugation of nature created, an onslaught that rooted the wild out of our homesteads, largely sterilizing the land. We are lamentably left without a connection through which we might learn our role in nature. To rediscover our part, we must let the wild creep closer in, then look for the subtle traces that will guide us on a walk in nature’s footsteps.

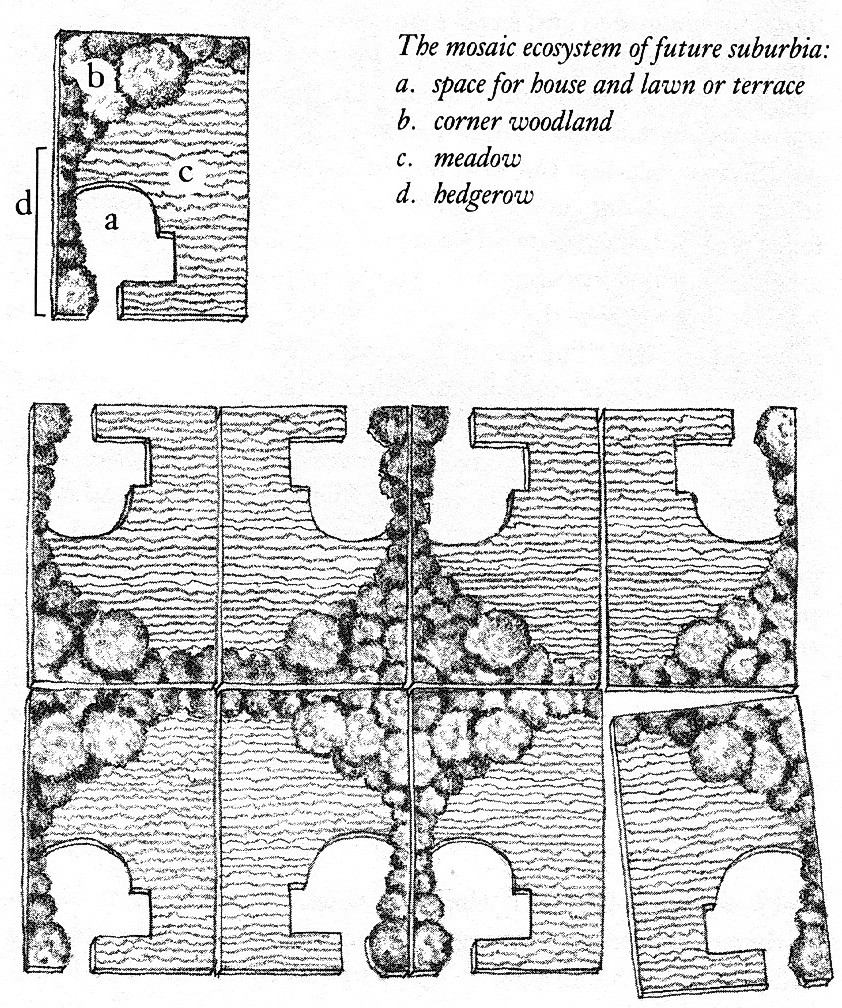

When we begin that walk, nature may appear wildly out of control, but all living beings are checked by natural limits that stabilize habitats. Conversely, human settlements create disparate, obstructive, artificial limits that inhibit species dispersion while generating segregated, unbalanced habitats. These unnatural limits are mostly physical barriers—walls, roads, buildings, parking lots, dams and large expanses of lawn—but they also include legal boundaries, like property lines.

Our assignment in this scenario is to conspire with plants to overcome these suppressive barriers, to become plant movers, traffickers in native plants. We can do this by collecting and transporting plants past the barriers and replanting them in ecologically appropriate sites. Foraging and transplanting disperses plants to new loci, and when properly done, the site of the foraging will self-heal. Digging plants gouges the earth’s surface and triggers a natural wound response. It energizes plant movement, drawing new seeds and sprouts toward the open wound—all to heal. It is life being kept by being given away, in nature, with humans and plants colluding.

Ancestral Connections, People and Plants

The collusion takes place in the welt6, a transitional zone where human culture mingles with the wild. It’s similar to the place where a meadow merges with an edge of forest. It’s a region of gathering where profuse plant and animal species make their home. The welt is a place where we humans may find our life’s work, and it is the origin of the native plant sharing network. It’s where remnant colonies of native plants store their ancestral memories. When we forage plants in the welt and ferry them into our yards, we spread and embed their memory in our neighborhoods. It’s plants going on as they must, with humans lending a hand. That lending transforms us, infuses us with the wild and reconnects us to our native roots as plant foragers. It continues the work of our forebears, gathering us back into an ancestral story that takes place on the edge of the wild. In that story we become part of the edge, facilitating the birth of new emergent edges, edges that grow in time to become foraging places for the next generation of people and plants. It’s forage-gather-plant, forage-gather-plant, an unbounded gift economy, a plant-led movement oblivious to maps and property lines, a cellular matrix of plants and people that knits us to ancestral memories while healing our disrupted, broken communities.

Foraging Honorably

Some may think that the concept of emergent edges invites a human free-for-all in the natural world. Surely, plant seeds blow freely in the wind and sprouts extend themselves freely through soil. Those movements are nature’s free-for-all, and we should join this movement. We must be vigilant, though, and exercise restraint when foraging plants. We are long separated, long isolated from nature; to harvest plants honorably, we must relearn to follow their ways. Undoubtedly, we have a stored living memory of how to follow plants and gather them sustainably. It’s in our DNA; indeed, it was once required for our survival. Still, for most of us, it’s a distant memory that has been buried and obscured by mental imprints of urban lots and suburban subdivisions that now swathe our modern landscape. For some, it’s the only landscape they have ever known; it’s the landscape that isolates them from nature, it’s the impoverished place where most or all of their nature schooling occurred. That schooling may have taught them about nature, but it could not possibly connect them with the wild. It was too distant. To make a connection, a different kind of schooling is needed, a schooling that takes place in the welt. I described such a school in an earlier post called “Working on the Edge of the Wild.” It’s an outdoor school where students learn to work in the welt, and part of that learning is how to forage plants properly. Foraging is honorable work; it must be guided by an etiquette that is passed on from those who came before us. We must learn to walk in the ways of the gathering place and all the beings who live there. To learn more about honorable gathering, please read my earlier post “Mother Yards and the Native Plant Sharing Network,” as well as “The Honorable Harvest” in Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass.7

Native Plant Nurseries

I want to end this post with some thoughts on our local native plant nurseries. These nurseries are essential to the success of our restoration efforts. We can find many native plants in the emergent edges of our communities, and this is the prime place for us to gather them. These local plants will be those best adapted to each neighborhood. In some cases, however, our native plants have been eradicated, and in other cases they are so greatly diminished that foraging would further endanger them. This is where our nurseries can serve the community. Their part is to enter the welt and carefully gather small quantities of the missing or low-supply plants to propagate and then distribute. Their role, like ours, must be guided by the plants. It is a supplementary role, but an essential one. The native plant sharing network will provide a base community for the nurseries, and they will ultimately benefit from that base. As plants are given to others through the network, it will create voids that draw more native plants into the matrix; it’s a source-to-sink movement, a natural movement of plants from locations of high concentration to those of low concentration, and one of the high supply places it will draw plants from is our nurseries. Generating that draw is key, and it is set in motion when we gather plants from our plenitude and give them to our neighbors.

It’s all part of a matrix that begins in the emergent edges and moves plants inward to heal the earth. It’s the self-conserving native landscape in action with plants leading—and humans following. The life blood of the movement is native plants; mother yards and native plant nurseries are the plant blood bank; and the native plant sharing network is the human community that gathers and disperses the plants. We were not meant to live on an island, segregated from nature. We are part of life’s emergent edge, part of life longing for life; a life that can only be sustained by being given away.

_______________________

1See Robin Wall Kimmerer, “Learning the Grammar of Animacy” in Braiding Sweetgrass, pp 48-59. A Google search will also bring up videos where she proposes the use of ki as personal pronoun.

2For more on this concept see David Abrams two books, The Spell of the Sensuous and Becoming Animal.

3This is another Robin Wall Kimmerer concept from the chapter “In the Footsteps of Nanabozho: Becoming Indigenous to Place” in Braiding Sweetgrass, pg. 210.

4 For more on this quote, see the chapter “Love Can Only be Kept by Being Given Away” in Thomas Merton’s book, No Man is an Island, pg. 4.

5The concept of life longing for life came to me through Stephen Jenkinson’s book, Come of Age.

6This is another Stephen Jenkinson concept. For more, see the chapter “The Fourth Temptation” in Come of Age, pg. 172.

7Another concept from Robin Wall Kimmer that spans the entire chapter, “The Honorable Harvest”, in Braiding Sweetgrass.

Many thanks to Emily Campbell for diligently editing the text in this post and for patiently working with me to clarify the ideas presented here. It was not an easy task. Thank you Emily!